Don’t wanna read? Watch the video instead!

Step 1: the initial question

I love wide angles, but my work has always moved across many focal lengths. From very wide to short tele.

So the question was simple: is there a way to change the look of the Leica Q without cropping and without pretending it becomes something it is not?

I had done something similar years ago with a Fujifilm X100 and its dedicated conversion lenses. That memory started everything.

Step 2: understanding conversion lenses

A conversion lens is an optical element that screws onto the front of a lens.

It is not cropping and it is not the same as swapping lenses. It physically alters the light path, introducing its own compromises, character and limitations.

They were originally designed to expand fixed-lens cameras without forcing a system change. Exactly the kind of solution I was looking for.

Step 3: the main problems

Very quickly, three issues became clear:

Almost all conversion lenses are out of production and now considered vintage.

Documentation is poor or non-existent. Often even sellers do not know what they are selling.

Most of these lenses were never designed for full-frame coverage, which means vignetting and quality loss were very likely.

From that point on, I started tracking practical details: thread size, physical dimensions, real usability, not just focal length claims.

Step 4: two working hypotheses

I moved forward with two ideas:

There should be at least one way to expand the 28mm both wider and longer.

Starting from a less wide focal length, like the Leica Q3 43mm, should make everything easier due to a narrower field of view.

Step 5: real-world testing

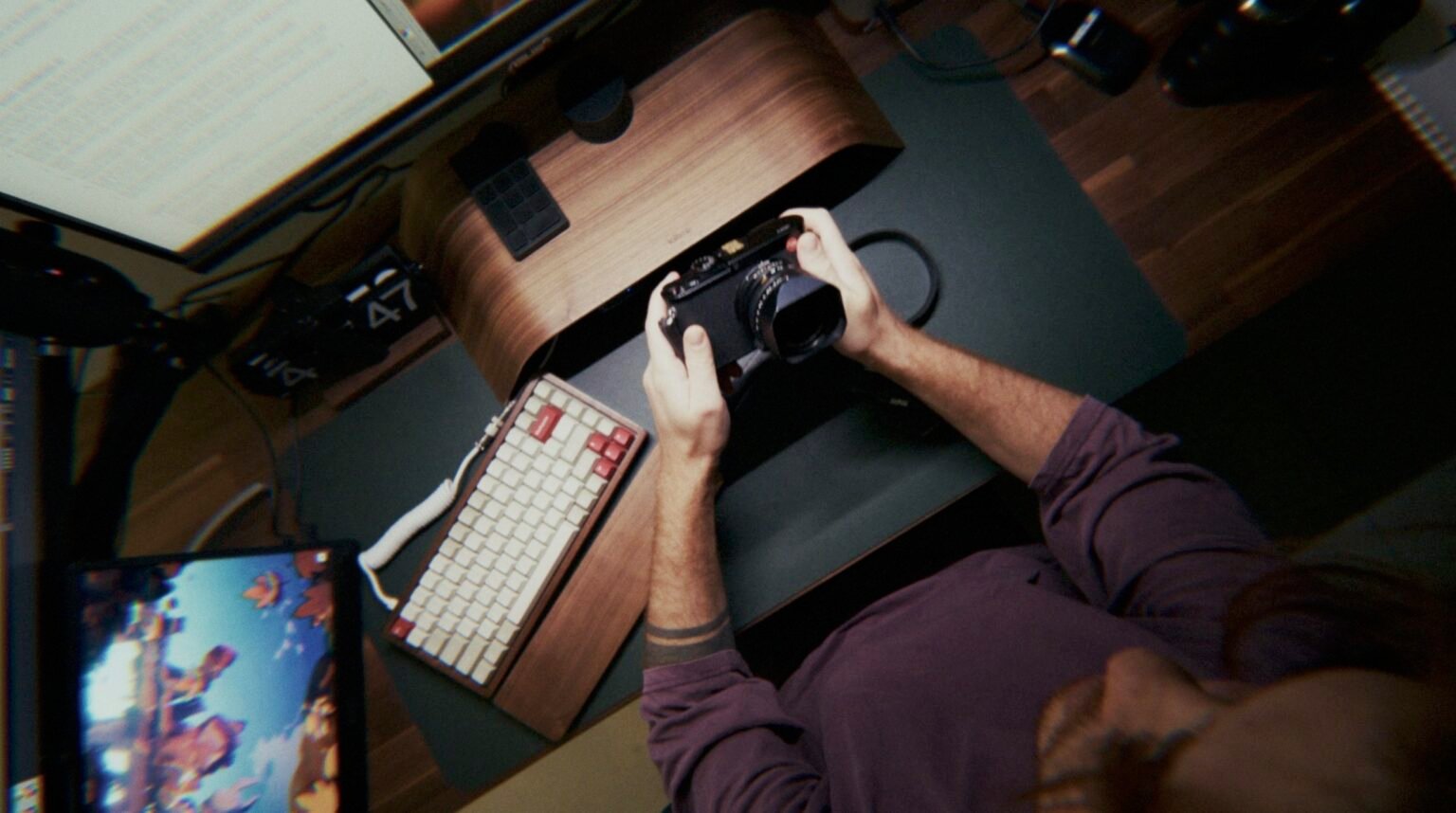

After about two months of research and purchases, I stopped testing at home and moved to real shoots.

During a shoot with Beatrice, I tested the most promising lenses with two questions in mind:

Do they meaningfully change the look of the image?

Can they be swapped quickly during a shoot?

At that stage, I was testing a wide conversion lens claiming around 0.43x and a vintage Canon tele conversion lens claiming around 1.4–1.5x, both with very distinct visual character.

Step 6: separating wide and tele

After more than three months, the pattern became obvious:

Wide conversion lenses on 28mm vignetted so much that they often looked like fisheyes.

Tele conversion lenses reduced the usable sensor area so much that a crop was unavoidable.

Still, one pair stood out:

Chinon 0.8x on the wide side, bringing the Q close to 20mm.

Sun Telenet Mini 35 on the tele side, bringing it close to 40mm with relatively controlled vignetting.

Unfortunately, the Chinon I found was in very poor condition and never became the clean solution I hoped for.

Step 7: the real breakthrough. The perfect lens

I kept thinking there had to be something like the Mini 35, but bigger.

That is how I found the Sun Telenet EE, originally made for the Canon EE system.

With a magnification factor of about 1.5x, it turns the Leica Q 28mm into roughly a 43mm. It is larger, but still portable, and its 55mm thread makes adaptation much easier.

Step 8: final field test

I tested the Sun Telenet EE and the Chinon 08 during a shoot with Silvia in Milan.

The Sun Telenet EE covers most of the frame, but it comes with compromises:

Strong light can create effects outside the frame.

Minimum focusing distance increases by about 20 cm, partially mitigated by macro mode.

Despite that, the result exceeded my expectations.

Sun Telenet EE Gallery - 42 mm

Chinon 0.8x - 22mm

Step 9: what the Q3 43mm confirmed

Testing the same lenses on the Leica Q3 43 confirmed the second hypothesis.

On 43mm, vignetting was much easier to control and overall quality held up better than on 28mm.

Final Note: this was never about finding a perfect or modern solution.

It was about experimenting, failing, testing, and understanding how far a fixed-lens camera can be pushed with a bit of ingenuity and a lot of patience.